Oxford – Mon Amour

It was love at first sight. Everything about this University city was magical, quite unlike Dhaka city in Bangladesh – my playground during wilder University days, or even London city where I spent first 2 days in England while undergoing initiation protocol at the British Council office. I was immersed into its inspiring architecture and culture and remain engorged in adaptation and reorientation during my wondrous and eventful days and never stopped admiring it. Even today, nearly half a century later, its charm beckons me to go there and take a trip in the memory lane, particularly visiting my Alma Mature, the Engineering Department. The body of this old and historical city has undergone various uplifts – at some locations unrecognisably, but its soul remains unchanged as beautiful as ever – still alluring and hypnotizing and, harkening me back to those earlier days – it’s truly Mon Amour.

I arrived in Oxford in Sept 1967 to read for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Science as a member of the Oriel College. My accommodation in a ‘digs’ in St John’s Street consisted of a small bedsit room with shared toilet and bathroom. It had a very sparse, not to say Spartan furnishings, which consisted of a single iron-framed bed, a rickety desk and a chair in front of the window and a chest of drawers with one of its knobs missing. Complaints? I had none whatsoever as I didn’t have any better back home. The weekly rent of 3 pound and 8 shillings included breakfast and one bath each week, any additional baths had to be scheduled in advance at an extra cost.

My first breakfast, brought in to my room by the landlady, consisted of fried egg and tomato with a piece of toasted bread and baked beans. This was a far cry from the spicy delicious curry and Paratha (flat Indian bread fried in butter), of which I was used to back home. The feeling of being served by a white lady, whose people were once our masters back home, was so uplifting that I even enjoyed this bland and tasteless breakfast.

I flicked through a folder on the table in my digs entitled ‘The House Rules’ – No smoking inside house; No baths without prior permission; No visitors in the room after 10 pm; No parties; No loud music; No bread crumbs on the floor No cooking in the room etc. To me all those were anathema, being used to an independent and unrestricted lifestyle before, but I was more than happy to accept and withstand all those restrictions for the privilege of being at Oxford and served by a white lady, a menial job for lowly maid servants back home. I even got my undue hair cut done by a white barber, a job only done by low-caste Hindus back home; just for the hell of it – self-glorification I suppose.

It was Saturday, first morning in Oxford. My designated mentor, Shaukat Khan, a fellow senior student at the same department, took me out. He pointed to a tall modern multi-storey building – the Engineering Department, stood out like a sore thumb within its traditional surrounding and informed me that it was, for all intent and purposes, going to be my home for the next few years. Inside the building he showed me my corner in the laboratory which I was to share with three other post-graduate research students, John and Peter – home students and, George from Greece.

I couldn’t wait to explore and soak up the atmosphere of the oldest and most prestigious city in the English speaking world, supposedly enriched by the harmonious architecture and the ‘Dreaming Spires’. I wandered along some of the narrow cobbled streets in the city centre passing various colleges. I was more interested in exploring the cloister-like colleges and experiencing the austere undergraduate life-style than the external aesthetics of the buildings. After all, I thought, in this highest seat of learning the robed students and teachers surely lead a monastic life, dedicated solely to pursuing knowledge like that depicted in Herman Hesse’s book, Glass Bead Game. But again, there would be plenty of time for that later, I thought. For the present I felt unable to concentrate on anything and I knew the reason – hunger pain. I was craving not just for any food, but for rice and curry – a Bengali without his fix of rice and curry for three consecutive days is indeed a desperate and dangerous man.

Like a sharp eyed hawk I caught site of a sign in capital letters, TAJ MAHAL RESTAURANT in Turl Street, with the inscription below: ‘Authentic Indian Cuisine’. Being a Pakistani I couldn’t possibly patronize an Indian restaurant as a matter of principle. Alas, I was so desperate that when the aroma of freshly cooked curry wafted through the open kitchen window and entered my nostril, ‘principle’ just flew out of my mind and I succumbed to my temptation and entered the restaurant. It was too early for lunch and I was hesitating when the waiter, Abdul, came to me and asked if I was looking for someone. When I said, I was looking for a meal of rice and curry, he ushered me to a seat and enquired with a grin in his face, if I was a Bengali. I wondered how he guessed that! A Bengali can recognize a hungry Bengali anytime, was his reply. A hearty meal of boiled rice, spicy chicken curry and Dal (Lentil curry) with hot green chillies and mango chutney as gratis, using my fingers made me feel – survival here wouldn’t be difficult. I also felt comforted having had a heartfelt chat in my mother tongue with the owner Ali, also a Bengali, from Sylhet district of the then East Pakistan. I was relieved to know that almost all Indian restaurants in this country were run by Bengalis.

Although fluent in written and colloquial English my apprehension of idioms was next to nothing and, that caused problems during my early formative days here. When I was invited to tea with my land lady, her daughter told me before her mother’s appearance at the lounge that she had taken a bit of a shine to me and if I played my cards right, I will be quid’s in.’ I had no clue as to what she meant by ‘A shine’ or “Play your cards” or “Quids”. During our conversation when I announced that I didn’t know how to play cards, the daughter was hiding her laughter with her scarf in the mouth while the landlady looked at me with bewilderment. Things turned out to be worse, when I complimented her by saying that she looked like my grandmother. On interrogation with a rather rude voice I explained that her hair colour was the same as that of my grandmother, i.e. white. Stunt, she taught me my first lesson of distinguishing between white hair and blond hair. Disgruntled – she warned me to mind my language and to get a grip into it sooner rather than later.

Similar misapprehension happened during my first encounter with my academic supervisor when he shook me by hand and said, ‘How do you do Sheikh’. I wasn’t sure to which particular activity was he referring? I decided to be cautious and replied nonchalantly, ‘In the same Bengali way as I always do, sir.’ Later I found out that my supervisor’s peculiar question was a common English idiom of asking how someone feels about life instead of saying simply, “How is you.” It took me some time to learn that this kind of peculiarity is the very meat and drink of the English language. After we’d exchanged a few more misunderstood pleasantries Walsh, noting me dressed in a black suit, told me that the department had a tradition of informality between the students and the academic staff. I asked what that meant. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘for a kick-off you can call me by my first name, instead of sir.’ I thought, ‘Kick off?’ Were we now going to be playing football, as a means of cementing our relationship?’ In my strong Anglo-Bengali accent I said, ‘No, no sir; I’m sorry. I absolutely cannot do that. According to my English primer back home, Donald was the name of a cartoon duck. You are my much-respected teacher and supervisor, how can I call you by your first name?’ From the expression of amusement in his face I could tell that once again he thought I was joking. Little did he know that people from the Indian subcontinent never make jokes at the expense of their elders and betters, let alone their teachers! For us, teachers are considered as the givers of knowledge and are regarded as gurus, i.e. virtual demigods, who command the highest respect. I couldn’t commit a mortal sin by addressing a guru by his given name, least of all when it was the name of a Walt Disney cartoon duck.

Following my contretemps with my land lady, I was beginning to realise what a minefield life in Oxford could be. Despite my best efforts to be polite and learn the ropes, I kept treading on mines. I didn’t have any alternative to learn the idioms to get by and survive. I was wondering why on earth he had asked me if I was going to attend a funeral – an extraordinary question, perhaps an idiom. Hoping to match him in levity, I shot back, ‘Why? Does the department provide funeral services, as well as education?’ Walsh smiled and rose to his feet. By now, one thing was perfectly clear, his sense of humour, which consisted almost entirely of mild irony, designed to unseat his interlocutors was the polar opposite of my own. Biding good bye at the door, he caught my gaze and said, ‘I should dress casually from tomorrow.’ I looked at his jeans and his scruffy jumper and said, ‘But you’re already dressed casually, sir,’ and, thought – why would he want to dress more casually, after all he is a professor!’ After a brief pause when he realized my predicament with the English idioms he said with a smirk before closing the door behind me, ‘I meant, if I were you.’ Outside in the passageway I stood for a few moments pondering on our last exchange – he was never going to be me, so why didn’t he just ask me directly to dress more casually!’ It dawned on me; I needed to get cracking with learning to decipher weird and rather wonderful idioms of English language, sooner rather than later.

Fresher’s fair at the Town Hall, just before the first session of the University’s Michaelmas term, was quite abuzz with starry-eyed freshmen like me. The older students were mostly minding their stands, trying to promote their clubs and activities and trying to recruit new members. I felt important and elated by the attention I received from many students vying for my involvement and patronage for their supposedly ‘noble’ causes. They were promoting a wide range of activities or ideologies from mundane, such as, ‘Save the Tree’, Animal Protection, Gay Right (the term ‘Lesbian’ was not in vogue then) etc., to some serious ones such as, Ban the Bomb, Human Right, Racial Equality etc. Additionally, there were religious and political groups, individual national groups such as Pakistani Student Association, Afro-Caribbean Student Association etc. Then there were some topical ones – almost ‘cult like’ such as, Therapeutic Drug Culture Society (following the cult of Timothy Leary), Monty Python Appreciation Society (MPAS- a weird-comical television serial) etc. I couldn’t resist the temptation of joining the MPAS. I thought it would be great fun without much involvement or waste of time. I attended the first of the MPAS’s impromptu meeting and became one of the organizers of the first and last ever mass ‘silly walk’ along the avenue of St Giles, a landmark of the city. It was a mimic of one of many weird and funny television sketches by the group by that name and was an emerging cult.

I woke up late on a cold Saturday morning – only about 8 weeks since my arrival in Oxford. I got out of bed and drank the cold coffee but didn’t feel like eating the cold breakfast. I casually opened the curtains and remained bewildered for a while by what I saw. For a moment I thought I was dreaming. It was a sunny morning alright, but everything was shrouded in a gigantic white blanket. I was no longer sure where I was. Dazed, I met my landlady on my way to the bathroom. She explained that there had been a very heavy snowfall the previous night and warned me of a repeat of the same, as par forecast, the next night. I sat on the chair and kept my gaze fixed along empty Pusey Street, musing on the exotic spectacle of snow-covered streets and houses. My first experience of seeing snow was absolutely mesmerising and thrilling. I went running outside to feel and touch the snow in my pyjama and slippers and was immediately called back by the landlady by the warning of catching pneumonia.

At the beginning we, the Pakistani students were trying to make friends with the students of the host community, particularly those having ‘Public School’ background. We thought that was the best way to learn the tricks. Alas, it didn’t work out for us quite as I hoped. Those students had their own circle of friends, toffs with posh accents and were mainly interested in sport, beer and women. Besides, the urge of exchanging jokes in one’s own language and to get involved in heated discussion about International as well as in one’s own country’s politics were inexorable. We just couldn’t do without regular ‘hang-outs’ in restaurants or cafés, known popularly in the Indo-Pak subcontinent, as “Adda ”and it became a life line for us all – particularly for the Bengali’s – most home seek species. Soon I found a corridor, secluded from the main dining hall of a second Bengali Restaurant, Motimahal for our regular dinner rendezvous. It was situated where the present mega shopping mall stands today. The area reserved for us, had the ambience, décor, food and service which made us feel as if we were sitting in a street side Restaurant Back home. Every evening we were there, having heated arguments about world politics while savouring a cut-price meal of a plate of rice topped up with a curry of our choice with lentil curry as a side dish. Fully satisfied, we went back to a goodnight’s sleep with home-sickness all but gone and world’s political problems – solved amicably.

I was not sure what to expect at the Fresher’s party at the Students’ Union. I was used to attend tea party or political party back home. I was amused to find boys and girls dancing, some holding each other’s hands. A few were simply drinking and nibbling finger food and chatting up – presumably a way of making friends and finding a girlfriend. I was tempted to dance, although I had never done so with a girl before. I was sure I could do what others were doing. But I didn’t know anybody and shied away from asking anybody to dance for the fear of refusal. Looking around I spotted a single Asian-looking guy whom I thought could be the person who had been mentioned to me by my mentor – a Bengali speaking fellow countrymen and the previous occupant of my corner at the laboratory. He was sitting on an armless chair flanked by a couple of pretty girls. He walked towards me leisurely and when right in front moved his pipe from his mouth with his left hand and extended his right one towards me and with a broad smile asked using the well-known cliché, ‘Rafi Ahmad, I presume!’ I stood up and while shaking his hand said, ‘You must be Asad Choudhury; I have heard quite a lot about you. I guess you are quite famous within the Asian student community here.’ He smirked, took his glasses off and with a twinkle in his amber coloured eyes said, ‘You need to take some lesson in English my friend. You probably mean, ‘infamous’, don’t you? He continued, ‘Yes, you have guessed it right; I have become a playboy and have forsaken the prestige of academic life. It is my choice. I hope you don’t follow suit. Mind you, I don’t advise you to lead a hermit’s life either. Best policy, my friend, is to work hard and play hard. This reminded me of my landlady’s advice. I simply hadn’t wanted to insult him by using the correct adjective. Anyway, I did take his advice and didn’t become a total hermit in pursuit of academic excellence during my Oxford days.

My idea of a monastic style student life at Oxford vanished as soon as realized that here, like back home, the undergrads had to work hard to meet deadlines for submitting their essays and dissertations and attend their lectures and prepare for examinations and try to get good grade and, all these are not particularly for acquiring knowledge, but to get good grade for better job prospect in the future. The first year of University for me was a time for familiarization, exploration, adventure and, most importantly, a time for personality building. There was much to do, learn and enjoy, but for most of us, beyond the chores of the academic works, there was precious little time for most of these. We had to be quite selective in our choice of involvement in non-academic avocations. Additionally, the local British Council office organized various cultural and recreational activities in its own auditorium on every Tuesday evening for the overseas students. Anybody associated with the University was encouraged to participate in those activities. Rolf, an enigmatic middle-aged German Jew was a regular visitor there and I met him for the first time in one of the events there. This amazing, amusing and, above all highly intellectual character befriended me and I spent a great deal of my spare time in his company during the busy and eventful Oxford days. He compelled me to listen to his life story during many eventful encounters, like the sailor in Coleridge’s epic poem, ‘Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner’.

The twilight period within the end of swinging sixties and the beginning of seventies brought in the pinnacle of events which took roots in mid-sixties. The pop culture with its Rock music came to a biblical status in Woodstock, Beatle mania and drug culture encouraged by likes of Timothy Leary spread over the English speaking world. Ordinary people of the industrial world took to streets for anti-Vietnam war demonstration and civil-right movement in the USA. First man landed on the moon and started a giant leap for mankind. The cold war reached its pinnacle, making an uncompromising North-South divide. While the north was enjoying unprecedented prosperity, the south was suffering famine of Biblical proportion. The world was changing in an accelerating speed; and all that was led and fuelled by the youths of that generation. Old values were undergoing re-evaluation and I was in the thick of it. While all these were happening in the wide world, I was cocooned in my small world of the adda circle with Rolf at the centre. I kept myself away from getting seriously involved in any international events; except for attending a meeting here and a demonstration there and completely preoccupied with my academic pursuit. I had long since abandoned the dream of changing the world; instead I was preparing to change myself – to get on board the floating world. My world at Oxford had never been dull but soon would be coming to an end. Time went by and appeared to be accelerating; I learnt the ropes at handling the English idioms and avoiding being odds with others and establishing good repertoire with the host community by and large. I learnt to dance, ask ladies for dates, acted as the General Secretary of the Voluntary Overseas Services Association as the sole foreigner in the committee, all without ignoring my academic commitments. I never forgot the words of my disgraced hero –‘Work hard’ and at the same time ‘play hard’.

Things were changing fast; activities at our Adda Khana (rendezvous) waned, some had abandoned it altogether. Instead of going to the Moti Mahal I started to pop in to the Lamb & Flag pub, just round the corner from my laboratory for my regular ‘chicken and mushroom pie’ lunch and had cooked dinner at my flat; thanks to my flatmate Aziz. I completed and defended my doctoral thesis in mid ’71 – the greatest relief in my life. However I was stranded at Oxford due to the outbreak of civil war back home. I got a short-term post-doctoral fellowship at the department and this enabled me to carry on working there and to publish a couple of papers. I had a reasonable income then and was no longer a perpetually broke student. I was aspiring to become a responsible professional man and trying to behave like one. I had a new circle of friends and most of us were pairing up with girlfriends. Rolf probably felt alienated in our presence, having no lady friend to accompany him to parties and functions. I maintained a good friendship with him and we continued to meet on and off, but our youthful exuberance and silliness and deep philosophical discussion sessions were things of the past – by then he had told me all about his life. I had become a senior in the eyes of the new students from the Indian sub-continent and was constraint to set good examples and earn respect.

The life style and composition of the student community from the Indo-Pak subcontinent had also changed since my early days in Oxford some four years earlier. Some of my intake had finished their studies and left, some were making preparations to go back home. New faces were arriving and forming their own circles for Adda. The Pakistan Association had ceased to exist. A very uncomfortable co-existence replaced the chummy relationship between the Pakistani students and us, Bengalis from the former East Pakistan at the end of the bloody civil war between these two wings of Pakistan. Now we had separate identities. The dinner time gathering for adda at the back of the Moti Mahal restaurant also had ceased. Freshmen were not as enthusiastic to join groups or societies which dreamt of changing the world. I could sense there was much more interest amongst the new-comers in more worldly things and were joining the computer user group, the popular science society, the literary society or the book club and a very few coming for pure research degrees. It dawned on me that the ebullience and ideology of the swinging sixties was slowly fading. A new generation of worldly wise students was in the making.

I eventually fell out with Rolf due to a sudden outburst of temper about something of least importance to me. I threw him out of my office corner at the department. He left me unceremoniously and that was the last time I saw him. I convinced myself that it was human nature to have a limited level of tolerance and that the occasional outburst of anger was an inevitable aspect of our humanity. I expected Rolf to take the initiative and seek me out to make amends. Both of us were too proud to sacrifice our ego and to apologise.

Estella and I got married at Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford. Rolf didn’t come to the wedding and didn’t reply to the invitation, although he had given us a Ming Vase as wedding present earlier. I settled down with a new job as a MoD scientist at a defence institute in a village called Shrivenham in Oxfordshire. After many years, during one of our regular visits to Oxford I felt an unstoppable urge to mend my friendship with Rolf by apologizing for my temper and hurting his feelings. I rang his doorbell. The gentleman who answered informed me that Rolf was dead – killed by a drunken motorist a year ago. The news was shocking and I felt being struck in the head by a hammer.

Although my obsession with Rolf’s life story and events in his company at Oxford was gradually fading, my resolve to write down his story narrated during our eventful days at Oxford became stronger than ever. I wanted others to read so that they would know about the man who wanted to ‘live on’ after his death. It is the story based on the life of a man who befriended me and captured my imagination and introduced me to a ‘brave new world’ filled with fine art, classical music and a deep quest for the origins of human consciousness and culture, appreciation for beautiful women and most importantly, he taught me to laugh loud under all adversity. He had held my imagination captive for nearly four years in Oxford and over five decades now.

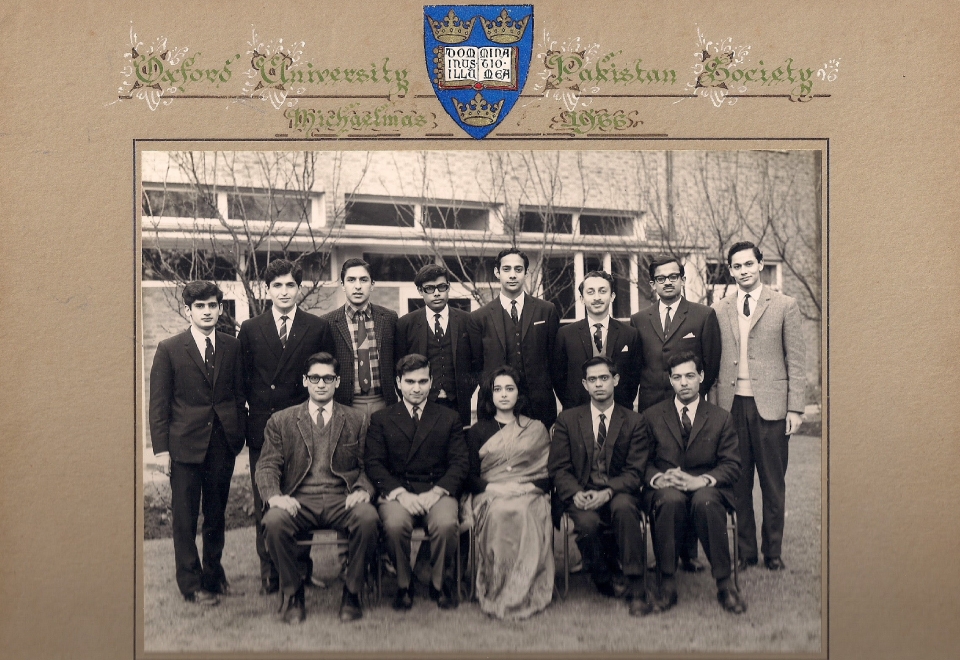

Oxford University Pakistan Society 1966

Oxford University Pakistan Society (Rafi is 3rd from the left) 1968

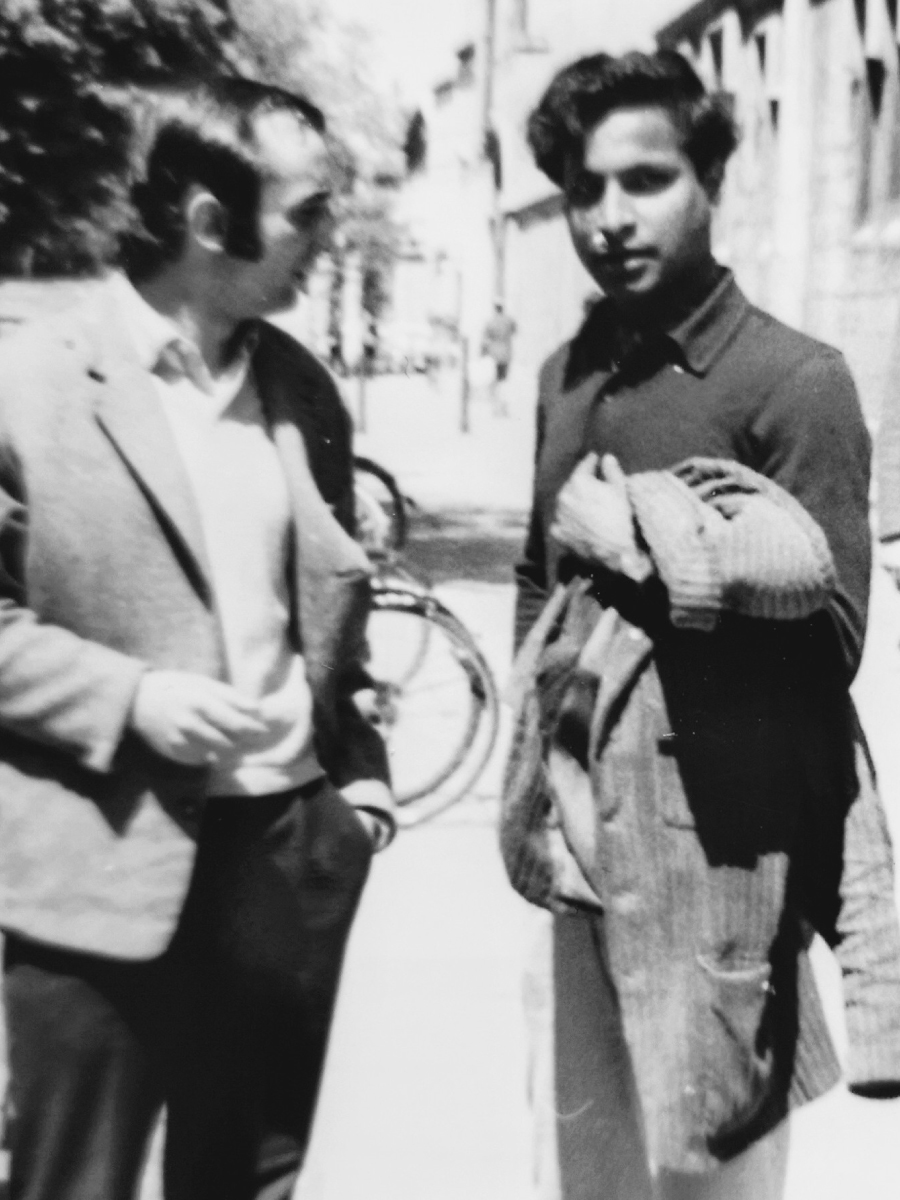

Rafi with G Ducous near St John’s College, Oxford 1969

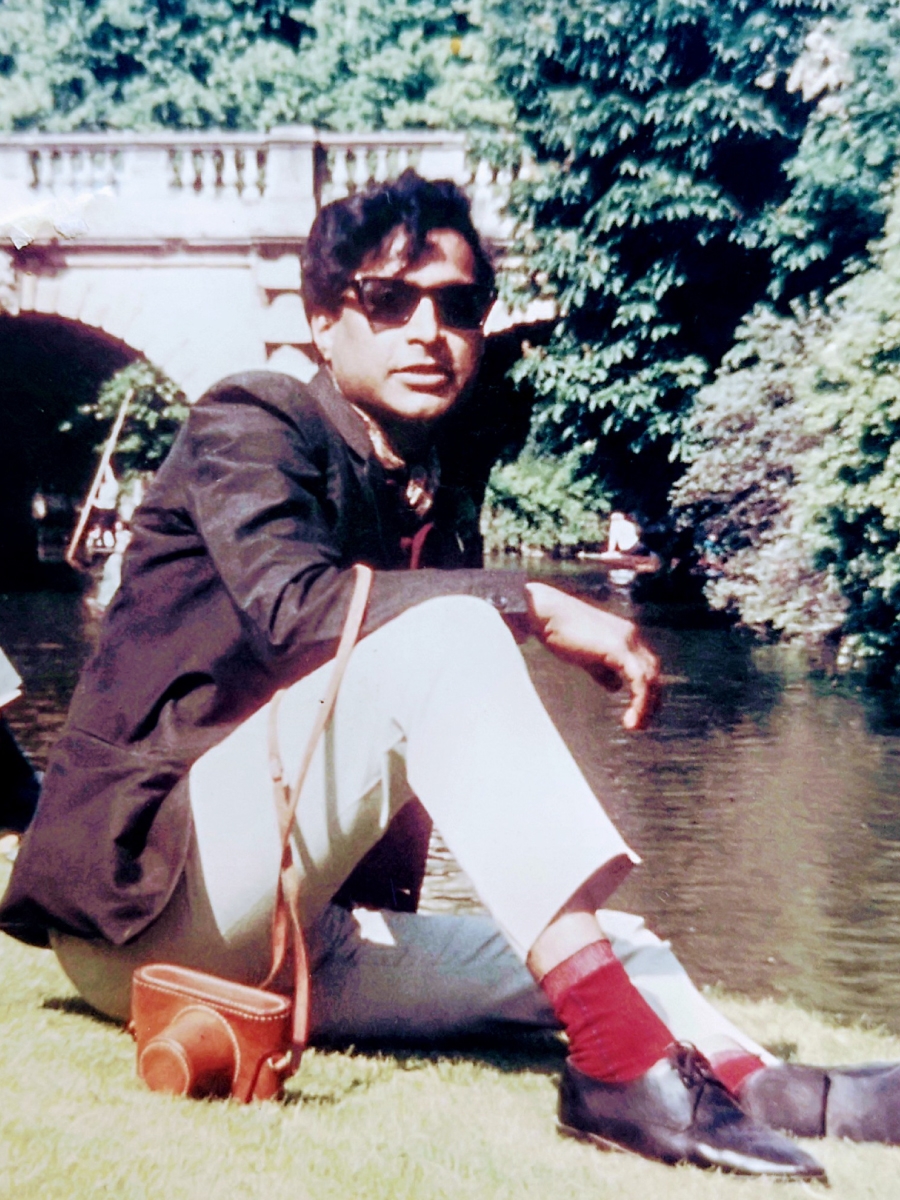

Rafi & Aziz by Magdalene Bridge, Oxford 1969

Rafi by Magdalene Bridge, Oxford 1969

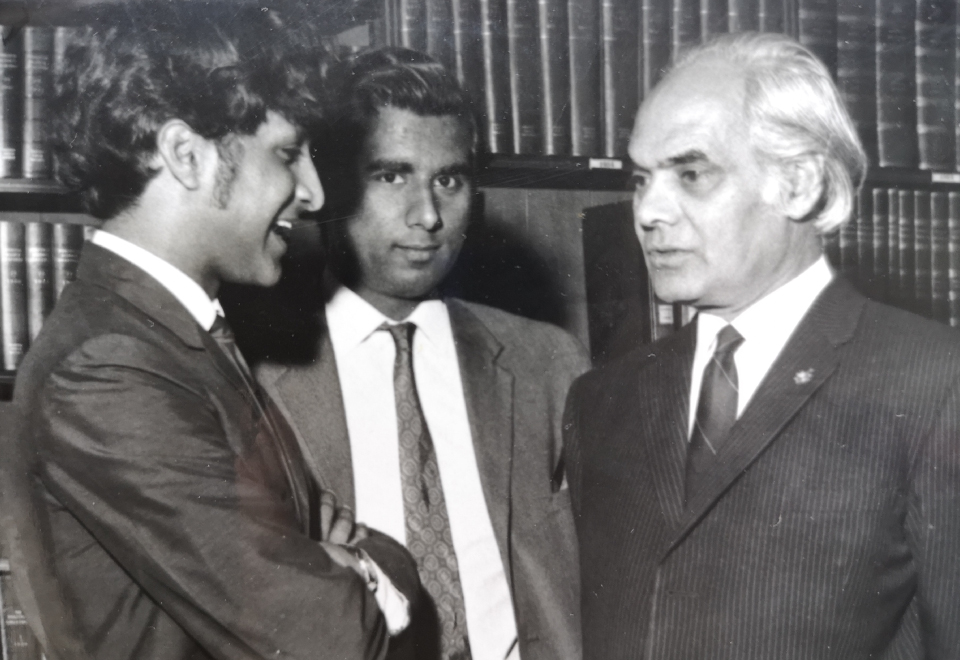

Rafi with the High Commission of Pakistan at Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford 1970

Rafi and Estelle, courting days 1970

Ming vase as a wedding present from Rolf

Copyright © S. Rafi Ahmad 2022-2025. All rights reserved.

Website by Bittersweet